When Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer began planning the Trade Union School of the General German Trade Union Federation (ADGB) in 1928, they already knew they would be completely designing the building from the inside (for the needs of those who would use the building) to the outside (the floorplan resulting from these needs). That all Bauhaus workshops would be involved was established from the outset—from the Building Department to the Finishing and Completion Workshops for Joinery, Metal and Weaving: everyone was to collaborate on this project. Here students would be able to deepen their theoretical skills and put these into practice directly on site.

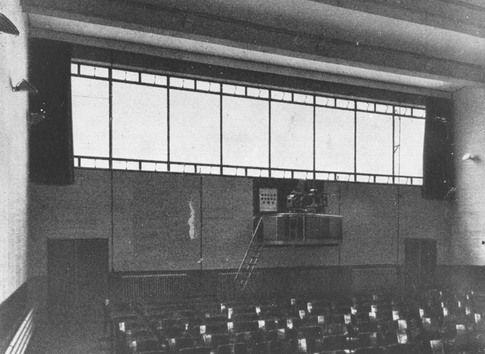

When the skeleton of the building was in place and the foundation of the square-shaped lecture hall rising over the one-story main building was completed, Meyer and Wittwer identified a fundamental problem with the space: there was a terrible echo and one could anticipate that noises coming from the adjacent dining hall would likely also create difficulties. The poor acoustics were a consequence of the cubic shape of the lecture hall, whose sides were of equal length (just over fourteen meters). The resulting effect can be described as a game of acoustic ping-pong. This phenomenon is still discernable today in the reconstructed Trade Union School lecture hall: the sound of hands clapping bounces off the walls and comes back to the listener multiple times. For events in particular this is of course less than desirable. In addition, the architects had only called for a single row of windows along one side of the lecture hall, just below the ceiling. As a result, the light coming from outside was somewhat unbalanced, even if sufficient for the functioning of the lecture hall. To counteract the undesirable echo effect and to evenly distribute light throughout the room, a material had to be found that could fulfill both requirements. But a material with these properties did not exist yet in 1929. So the Bauhaus quickly commissioned one of its best weavers to develop, as part of her thesis, the material needed for the Trade Union School lecture hall. This was the very material that would later become Anni Albers’s ticket to the newly founded Black Mountain College in the US when she was no longer safe as a Jew in Germany in 1933.

Anni Albers was a member of the Ullstein publishing family of Berlin. She arrived at the State Bauhaus in Weimar in 1922 with the intention of becoming a painter. When the Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925, she also moved to Saxony-Anhalt. In the interim, along with fellow students Gunta Stölzl and Benita Otte, she helped set up the weaving course at the Weimar State Bauhaus; its idiosyncratic, self-taught experiments with natural materials and new types of fibers turned it into the school’s “biggest hit.” The weavers’ innovations with fabric were based on the eventual users’ needs and functionality—nearly analogous to architectural designs from the building course. In the same way that architecture students translated their building-design analyzes into plans and schematics, weaving also became more science-based at the Bauhaus under Hannes Meyer’s directorship from 1928–30. Anni Albers’s diploma thesis is an outstanding example of this.

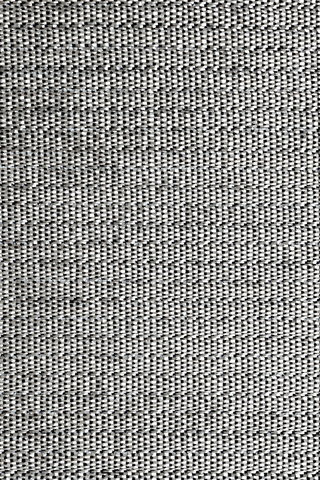

Sound dampening and light reflection were the parameters given for optimizing the Trade Union School lecture hall overall. Since no records of the fabric’s development have survived, it would be pure speculation to outline Anni Albers’s exact approach to her diploma thesis. However, as was common at the Bauhaus, she very likely experimented with various combinations and weaving strengths of various fibers until finding the ideal composition for her fabric that fulfilled the parameters in the best possible way. Based on fabric samples (small, ca. 10 x 10 cm pieces of fabric) still preserved today at The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation, MoMA, the TextielMuseum in Tilburg, Bauhaus Dessau Foundation and the Bauhaus Archive Berlin) it is easy to see how the weaver combined various fibers together to create a completely new effect: she used a cottony-soft chenille on one side for absorbing sound on the wall. On the inside, she wove together various densities of black cotton and transparent cellophane threads, creating a wavy structure. The fabric created from this combination has a metallic sheen, giving it the nickname “silver fabric,” even though—as sometimes mistakenly assumed—it contains no metallic threads.

To line the lecture hall, the ADGB commissioned the Bauhaus to produce 300 meters of the wall-hanging fabric developed by Anni Albers for ten Reichsmarks per linear meter, for a total of 3,000 Reichsmarks. The fabric was supposed to cover nearly the entire room. One-meter-wide lengths of fabric were affixed vertically next to one another on wooden strips and presumably also sewn together by hand along the edges by the Max Stapelberg company in Berlin-Steglitz. The lengths of fabric were three meters long each and abutted paneling made of Gabon plywood (a common and inexpensive building material at the time), which, like the wall hanging, ran around the auditorium and can also be found in the dining room, in the doors, and in the living rooms of the teachers’ residences. The lengths and widths of the fabric panels were presumably a result of the dimensions of the looms used at the Bauhaus.

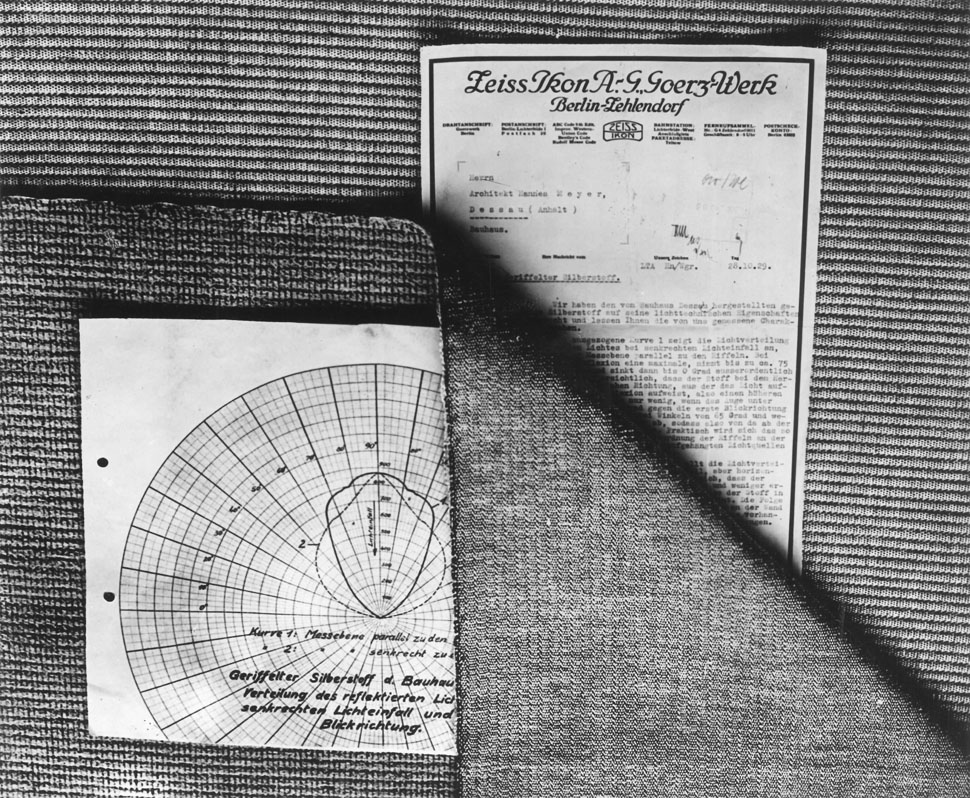

The effect produced by the 300-meters of silver fabric lining must have been quite impressive: a silver-shimmering wall hanging that distributed light throughout the lecture hall and at the same time adeptly absorbed noises coming from the surrounding rooms (dining hall and foyer). Using fabric to influence how light is directed was a bona-fide novelty in 1929. Camera manufacturer icon Zeiss analyzed the silver fabric, confirming to Anni Albers its now proven reflective ability. A photo of the fabric along with the certificate is rarely lacking from any of the numerous international publications on the Bauhaus—and is a preeminent example of the numerous new types of furniture and interior fabrics produced by the Bauhaus weaving workshop.

For the sake of thoroughness, it must be added here that, in addition to Anni Albers, a significant number of other Bauhaus weavers designed comparable fabric innovations, including Gunta Stölzl (who designed a waffle-structure fabric made of cellophane and cotton for the Kino Urban movie theater in Berlin) and Otti Berger (who patented a variety of washable upholstery fabrics). They documented and published many of their approaches in magazines in an effort to counteract weaving’s dated image and give it a modern look.

Anni Albers’s wall-hanging fabric adorned the walls of the lecture hall through the early 1950s, despite showing signs of significant wear and tear. Efforts by the school’s owner at the time, the Free German Trade Union Federation (FDGB), to develop the schools into the Trade Union College, coupled with increasing shortages of space in a building designed for 120 participants, lead to the demolition of the lecture hall in order to accommodate expansions to the dining hall, kitchen, and cloakroom. The lecture hall was reconstructed in part during renovations to the Trade Union School between 2002–07. The careful renovations already completed in most other parts of the building complex still need to be carried out here. This includes the silver fabric as well as the wood paneling, both of which have thus far only been color-marked and indicated. Today’s overall appearance of the lecture hall—in actuality a light-filled space with enhanced acoustics—is vastly different: a dreary place where visitors are compelled to ask why the renovations stopped here.

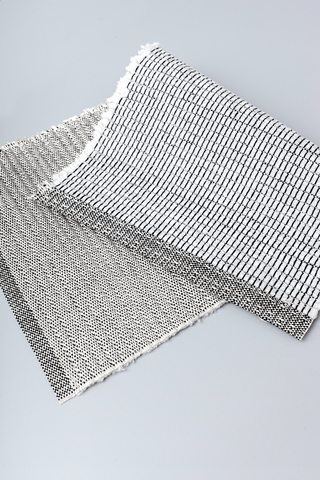

In the interim, The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation has commissioned the Berlin-based Dutch firm Jongeriuslab (located not far from today’s UNESCO World Heritage Site) to reconstruct the silver fabric. Its years of Bauhaus research and material experiments have paid off: the fabric developed by Jongeriuslab is astonishingly similar to that of Anni Albers’s. And a larger version of the small, preserved silver fabric samples gives an early idea of the fascinating effects the fabric would have on the entire auditorium. Of course, today’s sound-dampening and light-reflecting standards are no longer those of 1930, which have been far exceeded by new technologies and possibilities. And new requirements such as fire protection also play a major role in how public spaces are furnished.

A curiosity still remains for the lecture hall’s former modern and radiant look and the extent to which the silver fabric and Gabon wood panels would improve the acoustics. How things once were can already be appreciated in several locations of today’s UNESCO World Heritage Site following extensive renovations to the glass passageway, dining hall, conservatory, gymnasium and classrooms. Also still unresolved, however, is the overall image for Hannes Meyer and Hans Wittwer’s vision of the ideal educational building at this location.

Jongeriuslab (design) / Roel van Tour (photo), "Silver fabric", wall hanging fabric for the assembly hall of the Trade Union School, reconstruction, 2020, © Jongeriuslab, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Roel van Tour

Conversation with Siska Diddens from Jongeriuslab

In the 10th episode of the podcast KNTXT – Bernauer Stadtgespräche (Context –Cultural Conversations in Bernau), Siska Diddens, manager of the Jongeriuslab, talks about the long way from the original pattern of Anni Albers' "Silver Fabric" to its reproduction today. GERMAN/ENGLISH