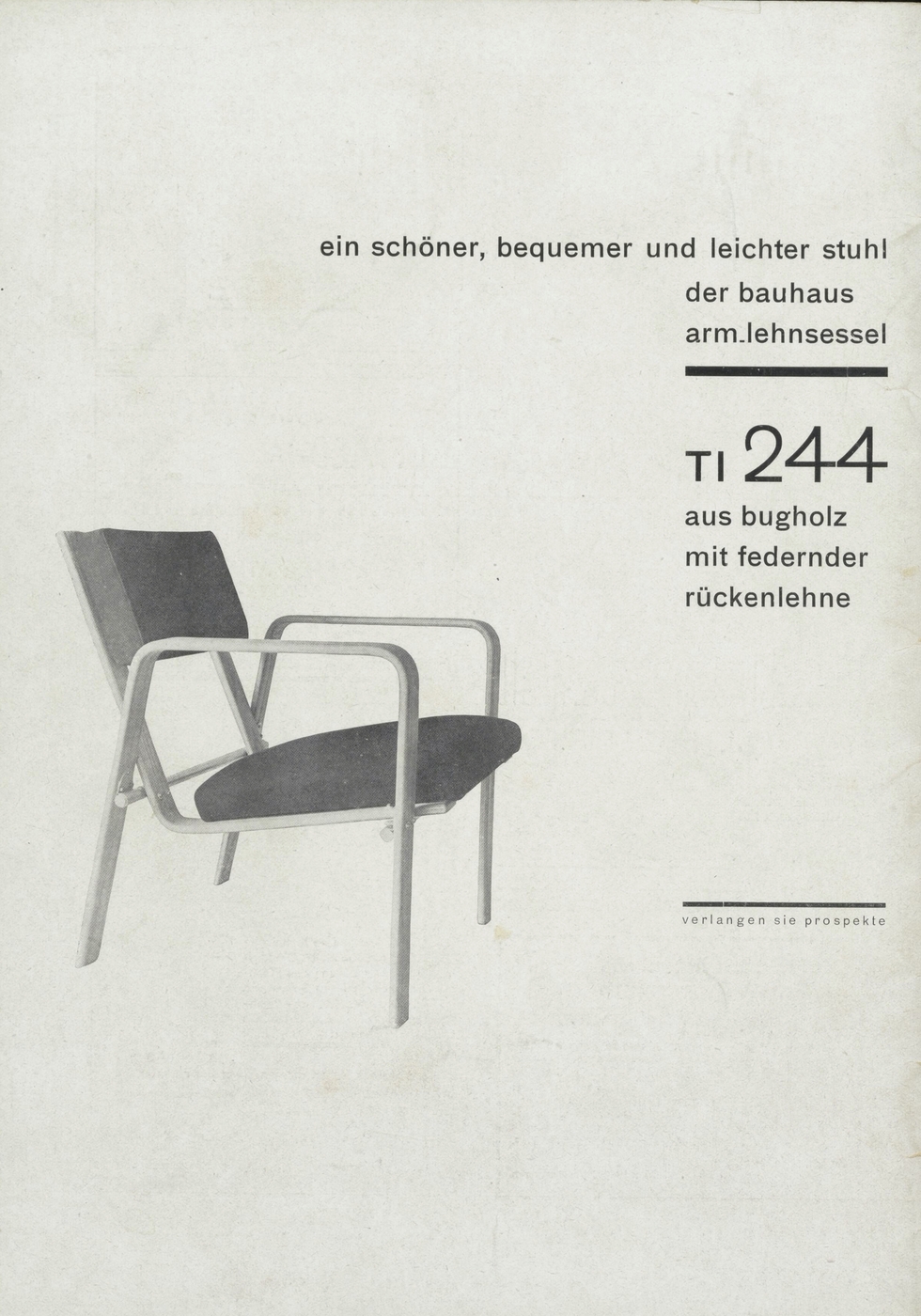

“Bent wood,” “springy backrest” and “spring cushions” are the catchwords associated with Josef Albers’s armchair number 244 manufactured by the Bauhaus carpentry workshop (Tischlerei or ti for short) on its tour of numerous exhibition venues for the Bauhaus traveling exhibition from 1929 to 1930. Mounted to a panel, it was possible to immediately grasp the ease with which the chair could be dismantled, the simplicity of its design, and also its space-saving attributes during transport. Albers anticipated with this principle what makes IKEA furniture so popular today. At certain exhibition venues an assembled copy accompanied this demonstration panel thus completing the overall impression. What sounds here like an auspicious Bauhaus design turned out to be somewhat of a sales flop. Its manufacturing proved too complex, making industrial mass production impractical. Preserved therefore are only individual examples from private estates of the ti 244 produced by Berlin furniture manufacturers J. C. Pfaff A. A. and Trunk & Co. through 1933. The primary intention in designing the ti 244 armchair was to make the leap from Marcel Breuer’s expensive, tubular-steel furniture to a “people’s chair” for everyone; but it failed due to its enormous ambitions. Little known until now is the fact that the ti 244 was also used at the Trade Union School – in a public building – for seating configurations.

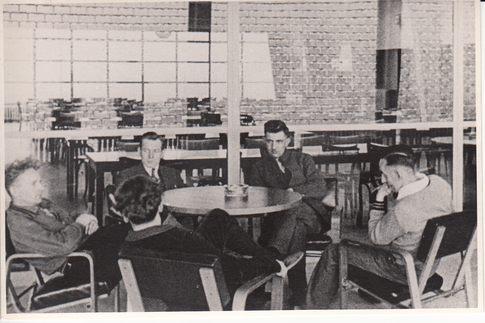

Preserved in the collection of the baudenkmal bundesschule bernau e. V. association are two photographs from the General German Trade Union Federation (ADGB) depicting two seating configurations with a total of eight Josef Albers armchairs identified by the number ti 244. They are seen in the lounge area located in the foyer of the Trade Union School, directly in front of the glass facade facing the dining room. The photos were taken during the operation of the ADGB Trade Union School between May 1930 and May 1933. It is a genuine new discovery that eight of the armchairs – which were invariably showcased as paragons of comfort and simplicity in exhibitions on furniture design under the directorship of Hannes Meyer at the Bauhaus (1928–30) – were part of the furnishing concept for the ADGB Trade Union School. To date, however, neither an order for the furniture placed with the Bauhaus nor any other similar information has been found in relevant archives. Brenda Danilowitz, chief curator at The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, had previously assumed that the ti 244 had never been used in a public building, relying in this case on statements and reports from Josef Albers himself.

The seating area in the foyer of the Trade Union School where the armchairs were used is also clearly indicated in the final plans: three round tables with a total of eight armchairs, represented as squares. The Josef Albers chair was accorded special status in all relevant furniture exhibitions at the time, with advertisements developed for its marketing and public presentation. However, the armchairs were not produced at the Bauhaus, but mainly by the Gemeinnützigen Arbeitsgenossenschaft Lübeck, a non-profit cooperative. Outsourcing the production of Bauhaus furniture designs to outside furniture manufacturers was a consequence of the consolidating of Bauhaus workshops to form a finishing department, which was conceived to complement the construction department (the architecture class). Following multiple complaints regarding quality-control issues, Meyer had quickly decided that small-scale commissioned productions should only be made by trained furniture makers and not by students. Instead the workshops were to focus on researching and analyzing new materials and using them to create new, experimental, lightweight and functional furniture. Ultimately, however, the full outsourcing of Bauhaus furniture production and marketing was never realized. The global economic crisis and the changing of the Bauhaus director (from Hannes Meyer to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe) prevented these ambitious plans.

What is certain is that the Josef Alber’s armchair ti 244 was accorded special status. The chair, made of four bent plywood strips and connected together by two steel support rods, was the most impressive item produced by the new Bauhaus furniture design under Hannes Meyer. It was specially featured in advertisements as such and displayed in every relevant Bauhaus exhibition between 1929 and 1930. Not least, the ti 244 became the visual symbol of the differences at the Bauhaus under Walter Gropius: luxury demands (Breuer’s cantilever chair made of expensive tubular steel and wire-mesh fabric or leather) versus popular demands (Albers’s armchair made of bent plywood and innerspring seat cushions). In Bernau, as a variation on the furniture from the lounge, it featured a seat and backrest covered with brown leather – another special feature – since the ti 244 was typically upholstered with dark fabric.

Furnishing the lounge exclusively with Bauhaus furniture was also planned: stools, chairs, and tables all featured the same basic support frame and varied in size. The frame is based on a 1927 design for a tea table by Josef Albers: four U-shaped elements with rounded ends, and two shorter ones for providing more stability. The round tables (a larger version of which was also used in the classrooms and the library at the Trade Union School) are the ti 204 folding tables featuring collapsible table tops and feet that could be pushed together. The chairs and stool – and presumably the ti 244 armchairs as well – were all upholstered with brown leather, which was easy to clean and robust.

Evident in the overall impression of furnishings at the Trade Union School – where Volkswohnungsdesign (dwellings designed for people), a term referencing the presentation of Bauhaus furniture in the Volkswohnung exhibition at the Leipzig Grassi Museum in 1929, was implemented in all rooms (tables, chairs, stools, beds), in combination with furniture and spotlights matching the Bauhaus aesthetic from other market-leading companies such as Thonet, Rockhausen, and Zeiss – is the full embodiment of “ideal construction” practiced by Hannes Meyer at the Bauhaus at the time. The planning and construction of the Trade Union School extended over the entire period of Meyer’s directorship, from March 1928 to May 1930. Here Meyer realized what he considered necessary at the Bauhaus: a hands-on collaboration on the building between all Bauhaus workshops.